|

Click to listen to this article

|

Does Wildfire Smoke Affect Potato Processing?

Wildfires in the Western U.S. are inevitable. This summer was no exception, as fires burned in all western states and many in the South. Record high temperatures this year and the ongoing mega-drought are not helping things. Dried-out soil and vegetation creates a tinderbox, just waiting for a spark. Mostly human caused, wildfires produce tremendous amounts of smoke, often making its way all the way to the East Coast and even across the Atlantic into Europe. Smoke destroys air quality and is particularly hazardous to those with cardiovascular or respiratory diseases, young children, senior citizens and outdoor workers such as farmers.

Wildfire smoke also affects plants. Smoke cover can modify local environments, creating temperature inversions and increasing diseases that favor cooler and wetter conditions like late blight. In addition to light-reducing particulates like black and brown carbon, wildfires also produce ozone, one of the most damaging air pollutants for plants. Leaves subjected to high concentrations of ozone can develop spots, known as leaf stippling.

Processing?

Wildfire smoke is harmful to humans and plants, but does it also affect potato processing? McCain Foods wants to find out. Addie Waxman, manager of agronomy with the company, noticed quality issues in some French fry varieties in very smoky years and wondered if wildfire smoke was the culprit. Waxman called on Mike Thornton with the University of Idaho, and a two-year study was secured, funded by a specialty crop block grant from the Idaho State Department of Agriculture.

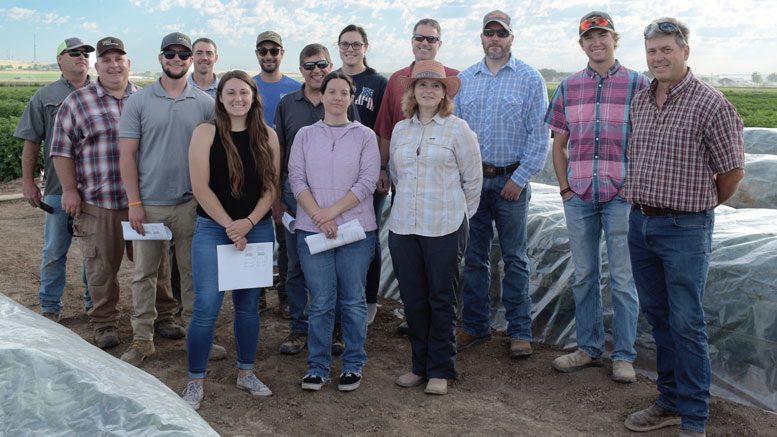

Thornton and his group at the Parma Extension Center in Parma, Idaho, are in the opening stages of a trial that reproduces smoke at extreme levels and pumps it into movable smokehouses they have built onsite. They are blasting three common processing varieties with smoke: Russet Burbank, Clearwater Russet and Alturas. The goal is to find out if some varieties are more sensitive to smoke than others during processing.

PM Me

Air quality index (AQI) is used to measure the concentration of fine inhalable particles in the air, known as PM2.5 rating. PM2.5 -ratedaircontains microscopic particles less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter, particles so small that they can be inhaled into the lungs and pose the greatest risk to health.

AQI can be pictured as a vertical bar with “zero” (good air quality) at the bottom. At the top is 300, which the EPA considers hazardous air quality, prompting a health emergency.

Thornton is blasting 500 PM2.5 worth of smoke on his plants. This is 200 points over the level at which the EPA suggests no one should be doing anything physical outside. This extreme 500-level versus a control group that is only using the air in Parma should see results, even in a heavy smoke year.

Par-Fry

The key to this project is not just smoking out the plants, but analyzing the final, processed product. Owen McDougal at Boise State University will test some par-fried (partially fried) French fries in his food chemistry lab and look at some of the chemical qualities of fries to determine if processing has been affected by the smoke. If it can be determined that one variety holds up better than others, and if a heavy smoke year is predicted, processors will be able to make recommendations to their growers about which varieties to plant to maximize end-product quality.

After two years, the researchers hope to have enough concrete results to get more funding and do even larger testing. Unless the West gets enough rain and snow to saturate the parched ground and break a historic drought, wildfires will remain a constant threat in summer and fall, making research like this vital to the ag industry.