By Bruce Huffaker, Publisher, North American Potato Market News

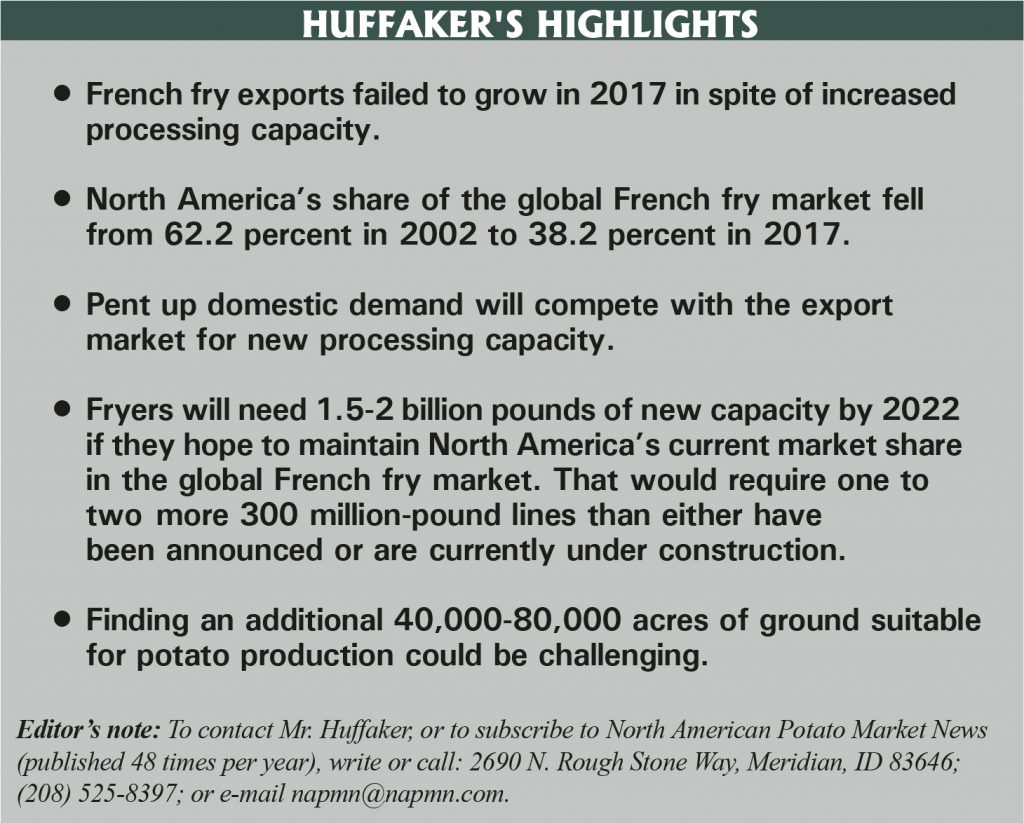

Recent expansion of North American French fry capacity is designed to facilitate export growth. So far, the expected growth has failed to materialize. During calendar year 2017, combined frozen potato product exports from the U.S. and Canada (excluding trade between the two countries) totaled 2.37 billion pounds. That is 17 million pounds less than 2016 exports, a 0.7 percent decline.

Several factors are contributing to the lack of growth in export trade, including stiff competition from European product, strong domestic demand for French fries and other frozen potato products, raw-product supply limitations and processing capacity issues. Each of these issues could be considered industry growing pains. In this article, we review some of the issues that the North American French fry industry faces in its efforts to ramp up production.

Global Market

In 2017, major exporters shipped 6.21 billion pounds of French fries and other frozen potato products to customers outside of their local trading zones. Local trade zones include North America (the U.S. and Canada) and EU-28 internal trade. The exports exceeded year-earlier shipments by 192 million pounds, a 3.2 percent increase. Last year was one of the slowest growth years that the industry has experienced in the past 15 years. Average growth during that time has been 8.1 percent per year. Nevertheless, the 2017 experience highlights some of the challenges facing North American fryers.

North America continues to lose market share in the global French fry market. In 2016, North American processors sold 38.2 percent of the product sold into the global market from the five processing regions we track. That is down from a 39.7 percent share in 2016 and from a 62.2 percent market share in 2002. It is not that exports have failed to grow during that time; they have increased an average of 4.6 percent per year. However, EU external exports have increased an average of 13.7 percent per year during that 15-year period. EU growth during 2017 was 8 percent. EU processors – especially those in Belgium and the Netherlands – have been in expansion mode during that time. They have focused on increasing exports to countries outside of the EU.

North American processors have ceded global expansion to their European counterparts, for the most part, until the last few years. They have focused on modernizing plants, with limited interest in capacity expansion. It has only been the last two to three years that the industry has shown much interest in expansion. It often takes two years or more to build a new production line, and longer to fine-tune it, so that it reaches its design capacity. Many older plants have been running beyond their design capacity in recent years. As new capacity has come online, fryers have had to take significant downtime on older plants to perform deferred maintenance and to refurbish equipment. That has limited production increases. It is likely to do so again for the 2018-19 processing season.

How much business has North American fryers ceded to competitors? If the North American market share had held constant at the 2002 level (62.2 percent), 2017 exports would have totaled 3.87 billion pounds. That is 1.49 billion pounds more than actual exports. It would have required five more 300 million-pound production lines to supply that volume. From a grower’s perspective, it would have required an additional 45,000-70,000 acres of potatoes to supply the plants, depending upon where the potatoes were grown.

Needed Expansion

How much expansion is needed during the next five years? That depends upon growth rates for both domestic consumption and the global market, as well as desired share in the global market. Let’s take a quick look at each of those factors individually.

The domestic market is much larger than the global market, but growth has been much slower. We estimate domestic consumption in the U.S. and Canada at approximately 11.1 billion pounds during 2017. After years of no-or-slow growth, demand has picked up in recent years. There is a substantial amount of pent up demand that awaits new capacity. Therefore, we will assume that consumption will increase by 2.5 percent per year in 2018 and 2019, followed by 1 percent growth for the remainder of the period. That would take domestic consumption to 12 billion pounds by 2022, a 900 million pound increase over five years.

Gauging the global market is more challenging. While it is possible that changes in tax laws and foreign exchange rates might allow North American product to be more competitive, capacity limitations make it unreasonable to expect North American fryers to gain market share during the next five years. We will assume that North American fryers intend to maintain their market share at the 2017 level of 38.2 percent. We will look at two scenarios. In the first, growth in global French fry demand slows to 5 percent per year. At a constant market share, North American offshore exports would increase by 656 million pounds, to 3.03 billion pounds, under that scenario. If the global market were to continue growing at an 8.1 percent average rate, North American fryers would need to export 3.5 billion pounds of product in 2022 to maintain their current market share. That is 1.13 billion pounds more than 2017 exports.

If fryers wish to maintain their current market share in the global market while supplying domestic demand, they will need to produce between 1.5 and 2 billion pounds more finished product in 2022 than they did in 2017. Current announced capacity expansion is between 1.2 and 1.3 billion pounds. That suggests that there is room for at least one to two additional 300 million-pound lines to be built during the next five years. That would still leave the industry running at close to capacity.

Supply Limitations

Raw product procurement could add to the industry’s growing pains. Fryers would need 25-33 million cwt more potatoes in 2022 to cover the projected usage increases. While yield increases might contribute a portion of the extra product, much of it would need to come from increased acreage – either new ground or ground shifted from table potatoes to processing use. Depending on where the potatoes were grown, needed increases could range from 40,000 to 80,000 acres or more.

While North American potato acreage cuts have been much more extensive over the past 20 years, finding enough ground to grow the extra potatoes may not be as easy as the numbers suggest. Much of the retired potato ground is in areas far removed from processing plants. A large portion of the ground is marginal and unlikely to come back into production. In addition, growers extended crop rotations as they reduced acreage. Processors currently require contract growers to be on a three-year minimum rotation. Unless they eliminate that requirement, expansion on current prime potato ground may be limited. The industry may need to pull ground away from other uses or find virgin ground (and the needed irrigation water to go with it).