By Bruce Huffaker, Publisher, North American Potato Market News

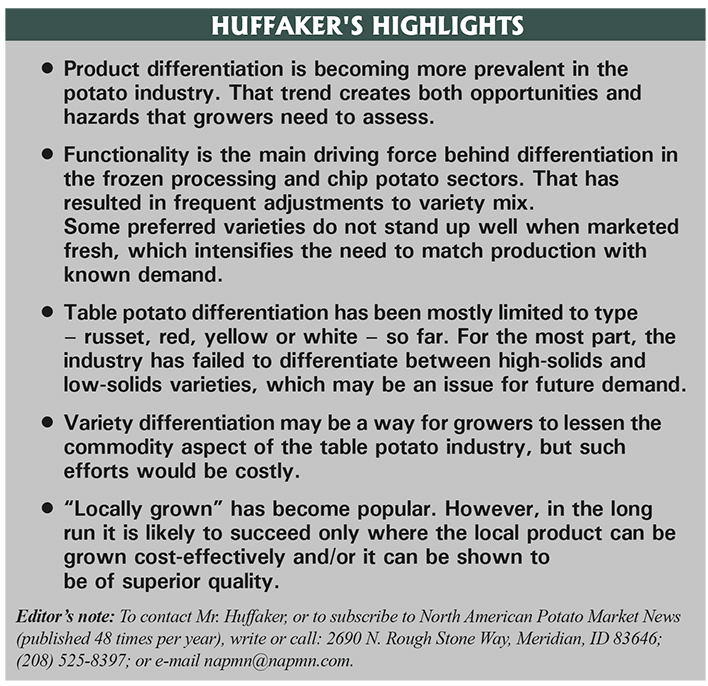

A potato is no longer a potato. While potato varieties still substitute for each other, to some degree, differentiation between types and varieties is becoming more pronounced each year. Buyers are demanding varieties specialized to meet their needs. At the same time, consumers are becoming more selective of the foods they eat, demanding more variety, and being more conscious about how and where their food is grown. These trends create challenges, opportunities and hazards for potato growers.

Processors and chip manufacturers always have had a preference for high-solids potatoes with low sugar content, which are traits needed to make premium products for their customers. In recent years, they have become even more selective. Many new varieties are designed to meet specific processing needs. In addition, some varieties previously used for processing have fallen out of favor due to pushback from customers or concerns that the finished product fails to consistently meet customers’ expectations. Both fryers and chip manufacturers try to contract for more than 90 percent of their needs to control not only the price of their raw product, but also varieties, quality and traceability.

Specialized processing potatoes often fall short of desired standards for table potatoes. This can be because handling practices vary between the table potato sector and the processing sector, or it can be the result of variety-specific issues. Whatever the cause, this makes it difficult to move excess chip and processing potatoes through fresh-market channels. When table potato supplies are short, packers and re-packers may consider handling marginal-quality processing potatoes. However, surpluses in processing potatoes usually coincide with plentiful supplies of table potatoes. Unfortunately, processing and chip potato surpluses can weigh on the table potato market, even if very few of them actually are moved through fresh market channels.

Table Potato Differentiation

In recent years, consumer interest in an increased variety of food has grown rapidly. That includes table potatoes. Russets still make up more than 70 percent of all U.S. fresh potato shipments. However, Russet Burbanks accounted for only 56 percent of russet shipments from Idaho’s 2016 potato crop. Burbank shipments from other russet growing areas were negligible. Nationwide, less than 30 percent of russet potato shipments are Burbanks. Consumers have been given little instruction on differentiating between high-solids varieties, such as Russet Burbanks, and low-solids russets, never mind the nuances between the various russet varieties that are being marketed. The resulting inconsistent performance of the russet potatoes they are purchasing may be contributing to the downturn in demand for russet potatoes.

Red potatoes have long been the largest non-russet table potato type for most of the country. In the past, there has been little effort to distinguish between red varieties. However, in recent years, yellow-fleshed red varieties have become a distinct sub-category. The red potato share of the table potato market has varied between 13.5 percent and 16.3 percent in recent years. The market tends to be highly seasonal, with the strongest sales coming during the spring and summer months when much of the crop moves directly from the field to market.

The availability of yellow potatoes has grown rapidly in recent years. Most consumers still think of all yellow potatoes as “Yukon Gold,” though that variety has lost favor with growers due to its lower yields and other agronomic challenges. Yellow potatoes accounted for about 7.5 percent of U.S. fresh potato shipments during the 2016-17 marketing year, up from 4 percent eight years earlier. Though there are a number of different yellow varieties, efforts to differentiate between them is still limited.

Sales of white table potatoes – both round white and long white – have been fading in recent years. Round white sales made up 2.7 percent of reported fresh potato sales during the 2016-17 marketing year, down from 4 percent eight years earlier. During the same period, the long white market share dropped from 2.3 percent to 1.4 percent.

The round white experience should be a cautionary tale for the potato industry. Most round white table potato varieties are low-solids varieties, referred to as waxy potatoes. In contrast, round white chip varieties are high-solids potatoes that tend to be much dryer when boiled. For a number of years, rejected chip potatoes went to re-packers, where they were packaged and marketed as table potatoes. The resulting inconsistent performance is one of the contributing factors in the downturn in demand for round white potatoes at the retail level.

Specialty varieties – fingerlings, purple potatoes, small potatoes – continue to grow in popularity. They are a small part of the overall table potato category. However, movement is likely to be understated, as many of these potatoes fall outside of standard USDA grading standards for potatoes. Therefore, most shipments from Idaho and Colorado don’t get reported through the regular reporting system. The situation for other growing areas is less clear. These potatoes tend to be branded items, which may include more variety differentiation than is afforded for the various color types.

Opportunities, Hazards

Origin has always played a role in table potato marketing – mostly it has been Idaho versus all other growing areas. However, in recent years, retailers have turned to “locally grown” products as an appeal to “socially conscious” consumers, who either want to support local farmers or believe that buying local produce reduces their “carbon footprint.” “Locally grown” is a flexible term. For example, potatoes grown in Dalhart, Texas, are marketed in Houston (680 miles away) as locally grown Texas potatoes. Nevertheless, the “locally grown” movement may offer opportunities for some growers to differentiate their products in certain markets.

Product differentiation creates both opportunities and hazards for potato growers. Opportunities for differentiation in the table potato market are numerous. Efforts to differentiate by variety are in their infancy. Creating demand for individual varieties may be costly, but the potential rewards could outstrip any added costs. The hazard is that as the market becomes more differentiated, it becomes more difficult to move surplus potatoes between usage categories. That makes it more imperative than ever that growers plan their production to meet known market needs, rather than attempting to grow as many potatoes as possible on the available ground. Growers also should be cautious about trends such as “locally grown.” If the local product meets high quality standards, with a reasonable cost structure, it is likely to endure well. However, if it cannot meet quality standards or if the cost structure is at odds with the laws of economics, growers may find that their customers tire of paying a premium to be “politically correct.”