|

Click to listen to this article

|

By Max Feldman, Collins Wakholi and Devin Rippner, USDA-ARS; and Bhoja Basnet, USDA/Cornell University Breeding Insight

Artificial intelligence (AI) may offer solutions to some of the diverse challenges faced in agriculture. AI is a bit of a catch-all term used to describe predictive modeling, classification, computer vision, natural language processing and autonomous system computing. Practically speaking, these tools enable us to forecast yield or profits from sample observations, identify product quality flaws, extract insights from text data, and deploy self-driving equipment like tractors and drones. Recent advancements in both computing hardware and accessibility are driving the rapid adoption of this technology in many sectors of our economy.

Limitations of Traditional Breeding

Unlike AI, plant breeding is an ancient process based on recurrent cycles of sexual hybridization, evaluation and selection. Applied plant breeding programs are labor intensive operations that routinely must generate, observe and evaluate hundreds to thousands of individuals and select those exhibiting superior combinations of traits. Our understanding of how traits are inherited is largely based on identifying statistically significant associations between observed phenotypes (size, shape, nutrient content, etc.) and DNA markers inherited from each parent using methods from the field of quantitative genetics. Linking this genotype and phenotype data is valuable to the breeder as it enables the process of molecular marker discovery and is the basis of predictive breeding methods like genomic selection.

Genetic improvement of potato through traditional breeding is challenging due to tetraploid genetics, slow rate of increase through clonal propagation and the stringent requirements of the consumer. Historically, potato breeding programs have heavily relied on brute force phenotypic selection to identify the highest performing clones from an initial breeding population of 50,000 – 100,000 individuals over an eight- to 10-year period. Initial evaluations are purely visual in nature and generally last less than a minute. Data on yield components, solids content, tuber shape, fry quality and defect susceptibility can generally be collected as early as the second field year with increased replication and additional field sites incorporated in later years. Although this process efficiently removes poor performing clones from the breeding pipeline, our inability to comprehensively and quantitatively evaluate many of the characteristics that influence cultivar adoption at early stages in this process limit application of the quantitative genetics methods that enable predictive breeding.

Potential of Artificial Intelligence

Perhaps surprisingly, evaluation of many of these important characteristics including tuber size, count, shape, skin and flesh color, fry quality, dormancy and susceptibility to defects can be performed through visual inspection. Humans are naturally good at recognizing objects from their characteristics and can use cognition to group objects into similar categories. Artificial intelligence models can also be trained to do this with high accuracy but at a rate of speed that greatly surpasses human capabilities. This capacity is tremendously useful in the field of quantitative genetics and plant breeding. Our ability to understand trait inheritance is dependent upon our ability to measure these features on a large number of related individuals (full or half-siblings). Technologies like image capture and artificial intelligence enable us to assess many characteristics simultaneously and at appropriate scale, while also reducing labor burden.

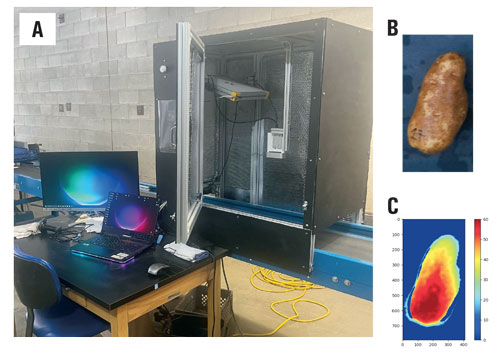

These principles have guided the USDA-ARS Potato Genetics Lab in Prosser, Washington, to develop an AI-powered potato tuber evaluation workflow that can be used to leverage predictive breeding in potato. Collins Wakholi, a postdoctoral research associate in Devin Rippner’s USDA-ARS soil science laboratory, constructed an AI-based data collection platform from consumer-grade hardware components including a belt-conveyor, image staging box with uniform lighting, RGB-D camera and GPU-enabled computer (Fig. 1A). This imaging system captures both a color image and depth map at a rate of 15 images per second while the GPU-enabled computer is using an AI model to detect and track the individual tubers across the imaging plane, saving a single cropped image and depth map of each tuber (Fig. 1B, Fig. 1C).

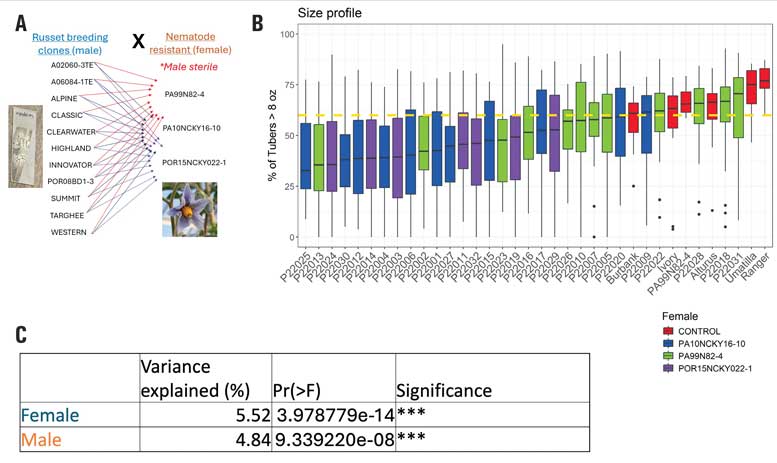

This enabled Max Feldman’s Potato Genetics Lab to evaluate many different characteristics on >1,500 breeding samples (32,000 lbs or >75,000 tubers) and draw conclusions about the inheritance of potato tuber size, shape, color and starch content from germplasm developed by the Tri-State Potato Breeding Program (Fig. 2). The simplicity of the design lends itself to other applications that utilize visual scoring techniques such as fry quality assessment and defect susceptibility.

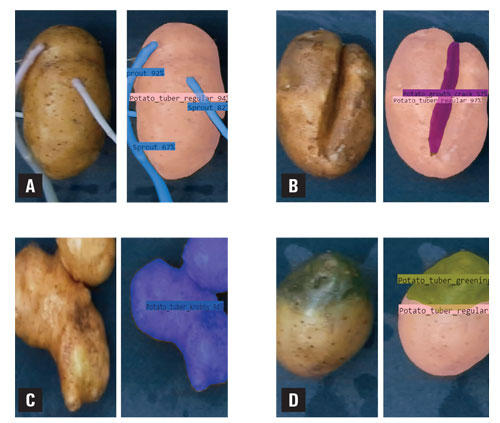

Another benefit of this approach is that data already collected for one purpose may be reused to train models that enable us to measure new features. USDA/Cornell Breeding Insight scientists Bhoja Basnet and Tyr Wiesner-Hanks utilized the partially annotated data collected from these studies to construct new models that can detect tuber defects including sprouting, growth cracks, secondary growth and greening with acceptable accuracy (Fig. 3). Breeding Insight is funded by the USDA, housed at Cornell University and levels the crop-improvement playing field by supporting USDA-ARS specialty crop breeders as they adopt data-driven tools and cutting-edge technologies in their day-to-day work. These models can be applied to new and existing data to glean additional insights and discover genetic variants linked with susceptibility to these defects.

AI enables us to learn more about a larger number of breeding samples than has ever been possible and makes the process much less toilsome. This alone will undoubtedly improve our ability to breed better potatoes.