|

Click to listen to this article

|

Despite possessing a suite of intriguing traits, Payette Russet and Castle Russet have been mostly overlooked by the potato industry since the Tri-State Potato Research and Breeding Program (PVMI) released them as new varieties a few years ago.

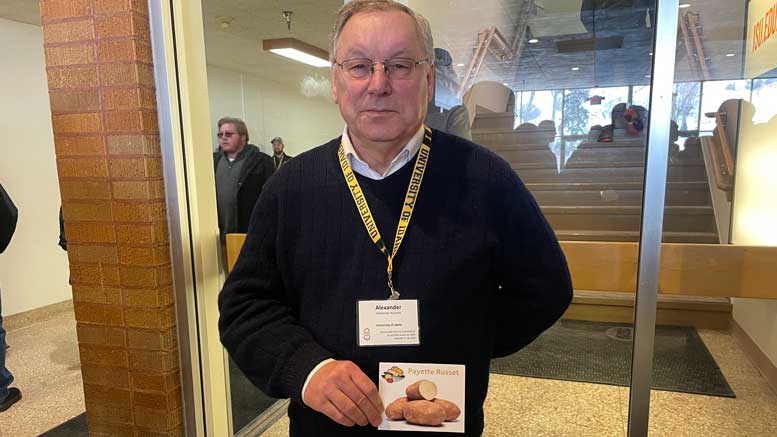

Though they’ve seldom been planted in commercial fields, a University of Idaho Distinguished Professor and potato virologist, Alexander Karasev, expects both varieties will fill an essential niche toward ensuring a bright future for U.S. potato production.

In March, Karasev and two of his former graduate students, Cassandra Funke and Lisa Tran, published a paper in American Journal of Potato Research, “Screening Three Potato Cultivars for Resistance to Potato Virus Y (PVY) Strains: Broad and Strain-specific Sources of Resistance,” finding Payette appears to have complete immunity to PVY strains. Karasev has begun similar testing on Castle, which contains the same R gene that confers resistance in Payette.

Based on the study’s findings, the two varieties should see broad use as parents within potato breeding programs seeking to overcome PVY, which is one of the most economically important diseases producers currently face.

“The availability of this R gene that was tested and verified gives the breeders a very good tool to move forward with,” Karasev said.

Karasev also sees potential to plant Payette along field borders, where aphids that spread PVY tend to feed first. Aphids lured to the Payette rows would potentially clean their stylets of the disease before moving to feed upon susceptible varieties.

Payette was crossed and selected from the U of I and U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperative breeding program in Aberdeen and released in 2015. Payette is often slow to emerge from dormancy following storage, which is a major reason why it hasn’t been widely planted. Castle is prone to a tuber defect known as hollow heart and also contains undesirable levels of glycoalkaloids — naturally occurring compounds found in Solanaceae family plants that could pose health concerns when consumed in high concentrations.

Potato Variety Management Institute (PVMI), which is a nonprofit corporation that handles licensing and royalty collections of potato varieties developed by a cooperative breeding program involving the states of Idaho, Washington and Oregon, have touted both Payette and Castle for their strong PVY resistance. Observations about the varieties’ PVY performance, however, were based on natural pressure in the field from common virus strains in the growing area.

Karasev and his team exposed Payette to 18 different isolates belonging to 13 unique strains and genetic variants of PVY from throughout the world. He maintains a collection of PVY strains in tobacco plants within a secure greenhouse, where his team conducted the Payette experiment. Sap from the infected tobacco plants was brushed on potato plant foliage.

“We have many strains of the virus that are not found in the U.S. We applied all of that when we tested,” Karasev said. “To my surprise, we could not break that resistance.”

In addition to Payette, he tested two control varieties that are highly susceptible to PVY. For comparison, he also tested two varieties with N-gene resistance, which is the most common type of PVY resistance gene present in commercial varieties. N genes trigger plants’ natural defenses to kill infected cells, but in some cases the virus can spread before infected cells die. As a result, prevalent PVY strains are constantly evolving and shifting toward strains that avoid resistance to specific N genes.

Karasev’s team used three to five individual potato plants to test each combination of potato cultivar and PVY strain, repeating the experiment several times at different times of the year.

The recent paper should provide breeders with surety that the R gene in Payette and Castle will hold up in the face of new PVY strains.

“Finding varieties with extreme resistance is one of the priorities of the breeding program because PVY can have an impact on yield and sometimes quality if the variety is susceptible to virus-related tuber defects,” said Rhett Spear, an assistant professor based at the UI Aberdeen Research and Extension Center specializing in agronomic and economic evaluations of new potato varieties. “A lot of work has been done by Idaho Crop Improvement Association and the seed growers to lower virus levels in the seed, but it’s just about impossible to eradicate it so finding varieties that are resistant is the best option.”

Karasev’s team started initial experiments on Payette Russet in 2018.

The work received some funding from a $5.8M USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Specialty Crop Research Initiative (SCRI) grant, called the Potato Virus Initiative, spanning from 2020 through August 2025, award No. 2020-51181-32136. Additional funding was awarded from USDA-NIFA Hatch Projects IDA01560 and IDA01712, USDA-NIFA-SCRI award No. 2014-51181-22373, the Idaho State Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block Grant program, Northwest Potato Research Consortium, Idaho Potato Commission and the Idaho Agricultural Experiment Station.