|

Click to listen to this article

|

By Ben Eborn, Publisher, North American Potato Market News

Factors affecting 2023 potato acreage are mixed. Growers have many things to consider when making planting decisions for this year’s potato acreage. Some of the major factors include current and projected potato prices, prices for alternative crops, projected production costs, contract volumes, irrigation water supplies, seed availability and crop rotations. In this article, we review some of the key factors influencing 2023 planting decisions.

Alternative Crop Prices

Record-high open market prices for the 2022 potato crop could encourage growers to plant more acres to potatoes in 2023. The average Idaho Russet Grower Return Index from October through December is $17.96 per cwt, up 73.4 percent from $10.36 per cwt a year earlier.

On the other hand, alternative crop prices are stronger than they have been in several years. USDA reports that the national all-wheat price averaged $9.12 per bushel during the October-December period, versus $8.41 per bushel a year ago, an 8.4 percent increase. All-barley and malting barley prices are up 38.6 percent and 42 percent, respectively. Alfalfa prices are up 11.6 percent across the country, at $241 per ton. Corn prices have jumped 24.2 percent to $6.52 per bushel, while soybean prices have risen 14.8 percent to $13.97 per bushel. Strong prices for alternative crops, coupled with rising input costs, could encourage growers to plant fewer acres to potatoes in 2023. The signals are mixed.

Production Costs

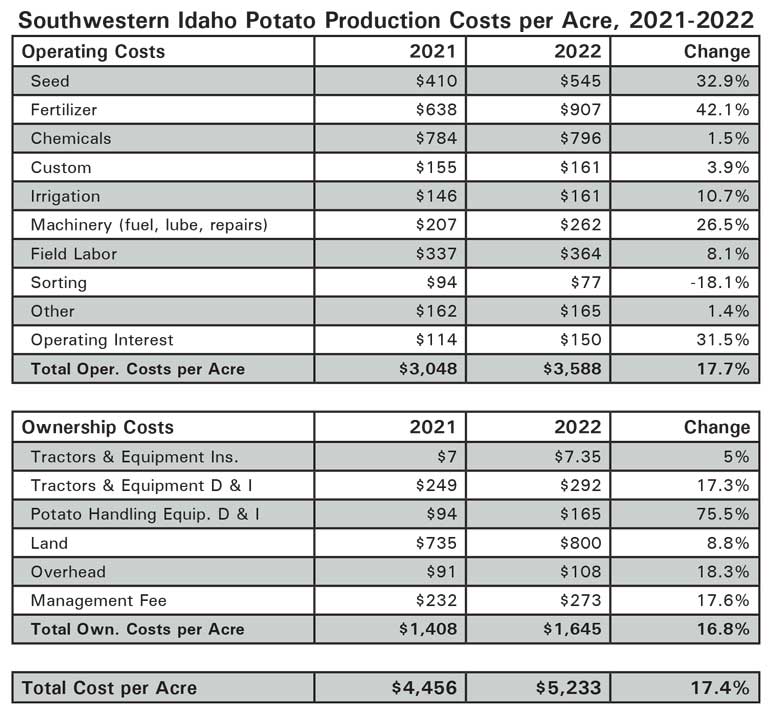

Potato production costs are expected to rise again for the 2023 crop, though the jump may not be as large as it was between the 2021 and 2022 crops. Table 3 shows the estimated 2021 and 2022 operating (direct/variable) costs and ownership (indirect/fixed) costs for potato production in southwestern Idaho. Operating costs per acre climbed 17.7 percent. There were significant cost increases last year for seed, fertilizer, irrigation, fuel and labor. Though fertilizer and fuel prices are currently lower than they were a year ago, other operating expenses are expected to increase in 2023. Labor costs and operating interest are likely to continue upward with rising inflation. Ownership costs are on the rise, as well. Overall, ownership costs rose 16.8 percent above 2021 costs, which put the total cost increase at 17.4 percent. Total production costs climbed as much as 20.3 percent in other parts of Idaho. Other growing areas faced similar increases. Idaho’s cost per cwt was up significantly more due to the 2022-crop yield reductions.

Machinery and equipment depreciation has been increasing with rising equipment and interest costs. A shift to mechanical sorting due to rising labor costs and workforce availability has encouraged more investment in mechanical sorting. Land rents have been receiving upward pressure as crop prices and farmland values have increased. Rapidly rising production costs and the uncertainty of product availability may cause growers to reconsider potato acreage expansion in 2023.

Other Factors

Several other factors could affect the 2023 U.S. potato acreage. First, processing contract volumes are likely to increase following three years of tight raw product supplies. Both domestic and export demand for French fries and other frozen products has been extremely strong. Frozen product imports from European processors have been record large. Strong finished product prices will encourage fryers to expand production in 2023 so they can maintain or expand their market share.

Second, irrigation water supplies could play a hand in Idaho’s 2023 potato area. Idaho’s irrigation water supply situation improved significantly during January. However, the Upper Snake River reservoir system is the lowest it has been, for this time of year, since 2004. Limited water might discourage potato acreage expansion, while a good water year could do the opposite.

Third, both growers and processors may be less confident in the potential for yields to continue trending upward, following the 2021 and 2022 experience. For the second year in a row, the expected production failed to materialize when the Columbia Basin experienced the third-coldest spring and the hottest August on record. Similar conditions held back yields in Idaho.

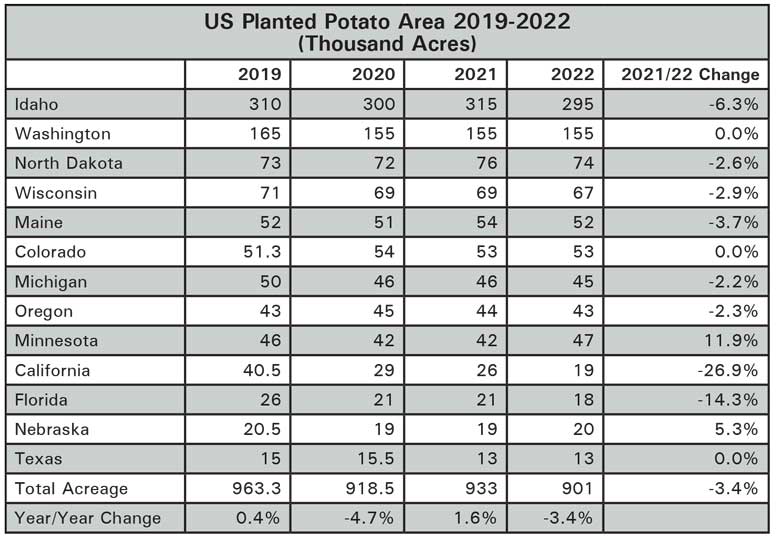

Fourth, crop rotation requirements typically prevent wide year-to-year swings in potato acreage. Shifts in acreage on a statewide basis are often more variable than the change in acreage on a national level. Year-to-year changes are typically less than 5 percent.

Finally, the country’s overall economic and political conditions may also weigh heavily on planting decisions. Growers across the country are considering the unique financial, production and market risks of growing potatoes this year.

Summary

There are several factors to consider when making planting decisions. Potato prices have been much stronger this year than they have been in the past; however, prices for alternative crops have also been strong. Rising production costs could continue to squeeze profit margins. Even with exceptional crop prices, the profit margins could be slim unless growers monitor costs closely. Other factors such as contract volumes, irrigation water supplies, yield variation, crop rotations and national economic conditions will play into planting decisions this spring.