By Rebecca Earle, University of Warwick

What we eat matters to us – but we’re not sure whether it ought to matter to anyone else. We generally insist that our diets are our business and resent being told to eat more fruit, consume less alcohol and generally pull our socks up when it comes to dinner.

The efforts in 2012-13 by New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg to ban the sale of extra large soft drinks failed precisely because critics viewed it as an intrusion into the individual’s right to make their own dietary choices. “New Yorkers need a mayor, not a nanny,” shouted a full-page advert in the New York Times. And when a school near Rotherham in northern England eliminated Turkey Twizzlers and fizzy drinks from its canteen, outraged mothers rose in protest, insisting that their children had the right to eat unhealthy food.

At the same time, many Britons are troubled by reports that as a nation their fondness for sugar and disdain for exercise will eventually bankrupt the NHS; there is considerable support for the idea that very overweight people should be required to lose weight before being treated. We agree that our poor dietary choices affect everyone, but at the same time we’re certain that we have a right to eat what we want.

The story about how we started to think this way about food is closely linked to the rise of the potato as a national starch. Britain’s love for the potato is bound up with notions of the utilitarian value of a good diet and how a healthy citizenry is the engine room of a strong economy. To find out more about that, we need to go back to the 18th century

Enlightened eating

Today’s somewhat uneasy marriage of public health and individual choice is the result of new ideas that emerged during the Enlightenment. During the 18th century, states across Europe began to rethink the bases of national wealth and strength. At the heart of these new ideas was a new appreciation of what we would now call public health. Whereas in earlier centuries rulers wished to prevent famines that might cause public unrest, in the 18th century, politicians became increasingly convinced that national strength and economic prowess required more than an obedient population disinclined to riot.

They believed it required a healthy, vigorous, energetic workforce of soldiers and labourers. This alone would ensure the success of industry. “The true foundations of riches and power,” affirmed 18th-century philanthropist Jonas Hanway, “is the number of working poor.” For this reason, he concluded:

… every rational proposal for the augmentation of them merits our regard. The number of the people is confessedly the national stock: the estate, which has no body to work it, is so far good for nothing; and the same rule extends to a whole country or nation.

“There is not a single politician,” agreed the Spanish thinker Joaquin Xavier de Uriz, writing in 1801, “who does not accept the clear fact that the greatest possible number of law-abiding and hard-working men constitutes the happiness, strength and wealth of any state”. Statesmen and public-spirited individuals therefore devoted attention to building this healthy population. It was the productivity puzzle of the 18th century.

The Potato Eaters (1885). Vincent van Gogh, Van Gogh Museum

Clearly, to do this required an ample supply of nourishing, healthy food. There was a growing consensus across Europe that much of the population was crippling itself with poorly chosen eating habits. For instance, the renowned Scottish physician William Buchan argued this in his 1797 book Observations Concerning the Diet of the Common People. Buchan believed that most “common people” ate too much meat and white bread, and drank too much beer. They did not eat enough vegetables. The inevitable result, he stated, was ill health, with diseases such as scurvy wreaking havoc in the bodies of working men, women and children. This, in turn, undermined British trade and weakened the nation.

Feeble soldiers did not provide a reliable bulwark against attack, and sickly workers did not enable flourishing commerce. Philosophers, political economists, doctors, bureaucrats and others began to insist that strong, secure states were inconceivable without significant changes in the dietary practices of the population as a whole. But how to ensure that people were well-nourished? What sorts of food would provide a better nutritional base than beer and white bread? Buchan encouraged a diet based largely on whole grains and root vegetables – which he insisted were not only cheaper than the alternatives, but infinitely more healthful.

William Buchan (1729–1805): ‘What a treasure is a milch cow and a potatoe garden.’ Wikimedia Commons

He was particularly enthusiastic about potatoes. “What a treasure is a milch cow and a potatoe garden, to a poor man with a large family!” he exclaimed. The potato provided ideal nourishment. “Some of the stoutest men we know, are brought up on milk and potatoes,” he reported. Buchan maintained that once people understood the advantages they would personally derive from a potato diet, they would happily, of their own free will, embrace the potato.

The benefits would accrue both to the individual workers and their families, whose healthy bodies would be full of vigour, and to the state and economy overall. Everyone would win. Simply enabling everyone to pursue their own self-interest would lead to a better-functioning body politic and a more productive economy.

The marvellous spud

Buchan was one of a vast number of 18th-century potato enthusiasts. Local clubs in Finland sponsored competitions aimed at encouraging peasants to grow more potatoes, Spanish newspapers explained how to boil potatoes in the Irish fashion, Italian doctors penned entire treatises on the “marvellous potato” and monarchs across Europe issued edicts encouraging everyone to grow and eat more potatoes.

In 1794, the Tuileries Gardens in Paris were dug up and turned into a potato plot. The point is that there were an awful lot of public-spirited individuals in the 18th century who were convinced that well-being and happiness, both personal and public, could be found in the humble potato.

These potato-fanciers never suggested, however, the people should be obliged to eat potatoes. Rather, they explained, patiently, in pamphlets, public lectures, sermons and advertisements, that potatoes were a nourishing, healthy food that you, personally, would eat with enjoyment. There was no need to sacrifice one’s own well-being in order to ensure the well-being of the nation as a whole, since potatoes were perfectly delicious. Individual choice and public benefit were in perfect harmony. Potatoes were good for you, and they were good for the body politic.

This, of course, is more or less the approach we take to public health and healthy eating these days. We tend to favour exhortation – reduce fat! exercise more! – over outright intervention of the sort that has seen Mexico impose a 10% tax on sugary drinks, or indeed Bloomberg’s soda ban.

Our hope is that public education campaigns will help people choose to eat more healthily. No one is protesting against Public Health England’s Eatwell Guide, which provides advice on healthy eating, because it’s useful and we’re perfectly free to ignore it. Our hope is that everyone, of their own free will, will choose to adopt a more healthy diet, and that this confluence of individual good choices will lead to a stronger and more healthy nation overall. But our modern belief that a confluence of individual self-interested choices will lead to a stronger and more healthy nation originated in the new, 18th-century ideas reflected in the works of Buchan and others.

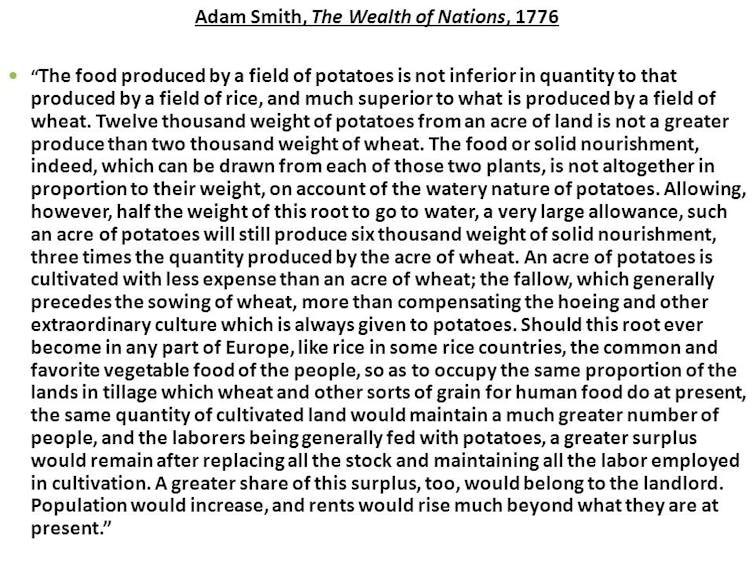

It is no coincidence that this faith in a wonderful confluence of individual choice and public good emerged at exactly the moment the tenets of modern classical economics were being developed. As Adam Smith famously argued, a well-functioning economy was the result of everyone being allowed to pursue their own self-interest. He wrote in 1776:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

The result of each person pursuing their own interest was a well-functioning economic system. As he asserted in his Wealth of Nations:

Every individual … neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it … he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.

Strong men and beautiful women

The best way to ensure a strong national economy, in the view of classical economists such as Adam Smith, is to let each person look after their own well-being. The worst thing the state could do was to try to intervene in the market. Interventions in the food market were seen as particularly pernicious, and likely to provoke the very shortages that they aimed to prevent. This rather novel idea began to be expressed in the early 18th century and became increasingly common as the Enlightenment progressed. As we know, faith in the free market has now become a cornerstone of modern capitalism. These ideas have profoundly shaped our world.

It was perhaps inevitable that Adam Smith should particularly recommend potatoes. His idea of the free market was premised on the conviction that national wealth was possible only when people were happy and pursued their own self-interest. Happiness and comfort, in turn, required a plentiful supply of pleasant and nutritious food – and this is what potatoes offered, in Smith’s view. Not only was the potato far more productive than wheat – Smith calculated this carefully – but it was also incredibly nourishing. As he noted, “the strongest men and the most beautiful women” in Britain lived on potatoes. “No food can afford a more decisive proof of its nourishing quality, or of its being peculiarly suitable to the health of the human constitution,” he concluded.

Smith linked the personal benefits individuals would derive from a greater consumption of potatoes to a greater flourishing of the economy. If planted with potatoes, agricultural land would support a larger population, and “the labourers being generally fed with potatoes” would produce a greater surplus, to the benefit of themselves, landlords and the overall economy. In Smith’s vision, as in that of William Buchan and countless other potato advocates, if individuals chose to eat more potatoes, the benefits would accrue to everyone. Better input of potatoes would result in better economic outputs.

In keeping with the individualism that underpinned Smith’s model of political economy, he did not recommend that people be obliged to grow and eat potatoes. His emphasis rather was on the natural confluence of individual and national interest. Indeed, potential tensions between personal and public interest were addressed directly by 18th-century potato enthusiasts, concerned precisely to see off any suggestion that they were subordinating individual freedom to collective well-being.

John Sinclair, president of the British Board of Agriculture in the 1790s, observed that some people might imagine farmers should be left to make their own decisions about whether to grow more potatoes. He conceded that: “If the public were to dictate to the farmer how he was to cultivate his grounds”, this might “be the source of infinite mischief”.

Providing information to inform individual choice, “instead of being mischievous, must be attended with the happiest consequences”. Advice and information, rather than legislation, indeed remain the preferred techniques for transforming national food systems for most policy makers. Nutritional guidelines, not soda bans.

The 18th century thus witnessed the birth of ideas that continue to be immensely influential today. The conviction that everyone pursuing their own economic and dietary interests would lead to an overall increase in the wealth and health of nations lies at the heart of the new, 18th-century model of thinking about the economy and the state.

Potato politics

It’s this idea – that private gain can lead to public benefits – that underpins the 18th-century interest in the potato as an engine for national growth. It also explains why during the 20th century, states and educational institutions across Europe established official potato research institutes, funded scientific expeditions to the Andes aimed at discovering new, more productive varieties of potato, and generally promoted potato consumption.

The British Commonwealth Potato Collection, like the German Groß Lüsewitz Potato Collection, or the Russian N.I. Vavilov Research Institute of Plant Industry, are reminders of this longer history linking potatoes, personal eating habits, and national well-being.

These connections between potatoes, political economy and a strong state moreover explain the current Chinese government’s obsession with potatoes. China is now the world’s leading producer of potatoes, which arrived in China in the 17th century but which have long been viewed as a food of the poor, while rice remains the prestige starch. For some decades, the Chinese state has been working to increase potato consumption and since 2014 there has been a particularly big push. There has been a great deal of pro-potato propaganda as regards both the cultivation and the consumption of the tuber.

Just as was the case in 18th-century Europe, this new Chinese potato promotion is motivated by concerns about the broader needs of the state, but it is framed in terms of how individuals will benefit from eating more potatoes. State television programmes disseminate recipes and encourage public discussion about the tastiest ways of preparing potato dishes. Cookbooks don’t just describe how potatoes can help China achieve food security – they also explain that they are delicious and can cure cancer.

One-third of the world’s potatoes are harvested in China. International Potato Center

As in the 18th century, in today’s China the idea is that everyone – you, the state, the population as a whole – benefits from these healthy eating campaigns. If everyone pursued their own self-interest, potato advocates past and present have argued, everyone would eat more potatoes and the population as a whole would be healthier. These healthier people would be able to work harder, the economy would grow and the state would be stronger. Everyone would benefit, if only everyone just followed their own individual self-interest.

The 18th century saw the emergence of a new way of thinking about the nature of the wealth and strength of the nation. These new ideas emphasised the close links between the health and economic success of individuals, and the wealth and economic strength of the state. What people ate, just like what they accomplished in the world of work, has an impact on everyone else.

At the same time, this new commercial, capitalist model was premised fundamentally on the idea of choice. Individuals should be left to pursue their own interests, whether economic or dietary. If provided sufficient latitude to do this, the theory runs, people will in the end choose an outcome that benefits everyone.

A small history of the potato allows us to see the long-term continuities that unite political economy and individual diets into a broader liberal model of the state. It also helps explain the vogue for the potato in contemporary China, itself undergoing a significant reorientation towards a market economy.

The connections between everyday life, individualism and the state forged in the late 18th century continue to shape today’s debates about how to balance personal dietary freedom with the health of the body politic. The seductive promise that, collectively and individually, we can somehow eat our way to health and economic well-being remains a powerful component of our neoliberal world.![]()

Rebecca Earle, Professor of History, University of Warwick

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.