By Mike Thornton and Nora Olsen, University of Idaho

It’s really a very simple formula: increase the length of the growing season and increase the potential yield and profits from a potato crop. There isn’t much that can be done to avoid a season-ending frost sometime during the fall, so perhaps the most feasible way to extend the season is to plant the crop early. With the stocks on hand report indicating tight supplies of potatoes this spring, there may be even more pressure to get into the field early in 2020 in order to take advantage of higher prices for early harvested potatoes. These are both good reasons for growers to consider planting early, but when making decisions on when to start planting growers should be aware that there are also some substantial risks involved.

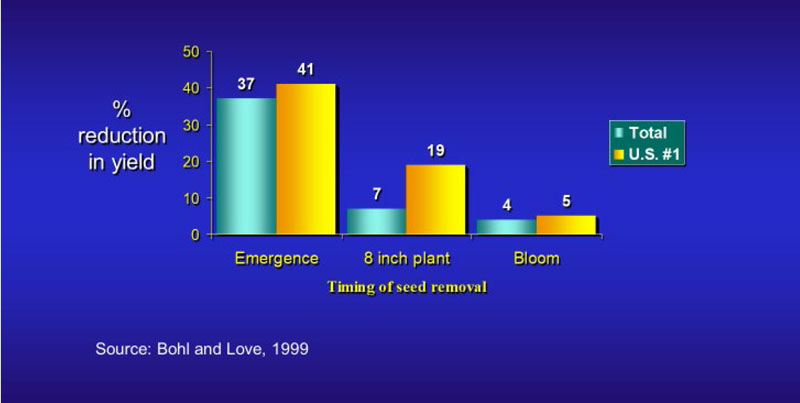

When you plant potatoes you start a race between the disease organisms that are trying to infect the cut surfaces and wounds of the seed piece, and the tuber tissue that is trying to heal those injuries and produce sprouts that will form vigorous plants. The plant depends on the seed piece for energy and nutrients for quite a while after emergence. Research has shown that the longer the seed piece remains intact, the more productive the plant will be (Figure 1). Ideally, the seed piece should remain sound until the plant has a chance to utilize all the nutrients and energy stored within it. The seed piece provides a large portion of the plant’s nutrient and energy requirements up until they grow to be about 10 to 12 inches tall. At that time, they have enough leaf area and root system to support plant growth.

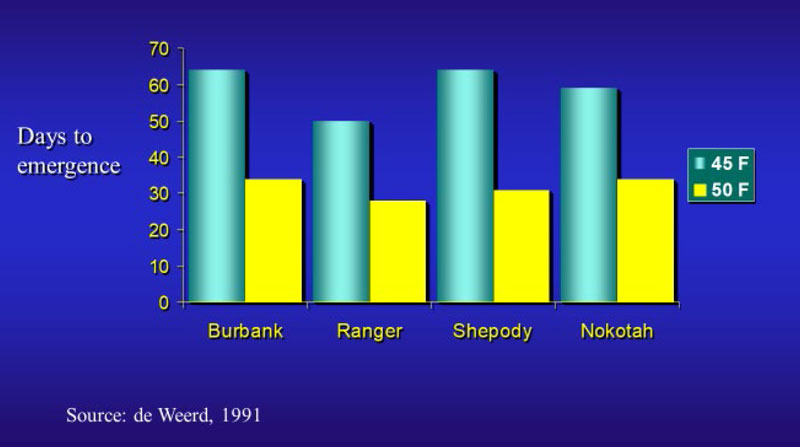

To minimize seed decay, it is important to plant at temperatures that promote healing of cut surfaces and encourage rapid sprouting and emergence. There is an old rule of thumb that soil temperatures at seed piece depth should be above 45oF and climbing before starting to plant seed (Figure 2). This temperature threshold is especially important for cut seed because of the large surface area that must undergo wound healing. Soil temperatures below 45oF prevent wound healing.

Rate of plant emergence is also greatly delayed by planting in cold soils. There is a direct relationship between soil temperature and days to emergence (Figure 3). For example, Russet Burbank plants emerge in 20 to 25 days at 50oF but take more than 40 days at 45oF. The bottom line is that the longer a seed piece sits in the cold soil, the more likely that it will decay before producing a healthy plant that will survive and produce a good crop. The effects of cool soils can be partly overcome by warming seed before cutting and planting shallow to promote rapid emergence. Applying a fungicide treatment also helps protect the seed from decay, but it cannot completely overcome poor management decisions that result in the seed piece being planted in unfavorable soil conditions.

Figure 3. Effect of soil temperature (45 versus 50oF) on days to emergence of four potato varieties.

Note that the information in Figure 3 indicates that some early maturing varieties tend to be very sensitive to the cool soil conditions that commonly occur in early-planted fields. For example, Shepody emerges slightly sooner than Russet Burbank at 50oF soil temperature but takes a few days longer to emerge at 45oF. Combine this with the fact that some of these varieties also tend to wound heal at a slower rate, and it becomes apparent that early planting may not provide the best seed performance when soils remain cool for extended periods. Planting in cold soil can also be hard on Russet Norkotah as slow early growth can translate into reduced leaf production and smaller plants.

One way to minimize the dangers of seed decay for early plantings is to plant whole seed or seed that has been cut and allowed to heal (suberize) before planting. The intact skin of whole seed and the healed surface of suberized seed are very resistant to seed decay and can greatly increase the chances of establishing a good stand. Seed piece treatments are still recommended for control of Rhizoctonia and sliver scurf as well as fusarium dry rot in both whole and healed seed. Whole seed may need to warmed for a couple of weeks prior to planting to ensure that the seed tubers will produce the desired number of stems per plant. The impact of warming on stem numbers and plant performance will vary by variety.

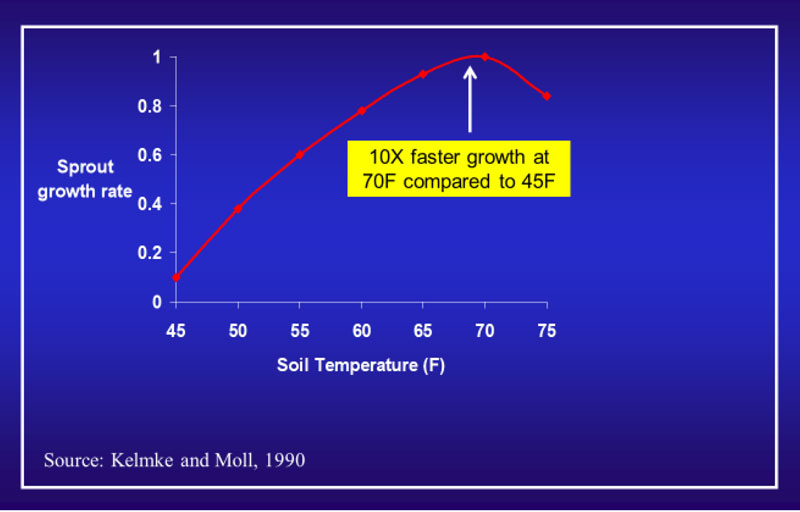

As if delayed emergence and increased seed decay weren’t enough to worry about, Rhizoctonia stem canker, frost injury, and higher incidence of physiological disorders such as brown center/hollow heart should also be considered when making decisions about when to start planting. Rhizoctonia is favored by cool soil conditions because the sprout tissue is more susceptible to infection prior to emergence of the first leaves. Sprout growth rate is directly related to soil temperature (Figure 4), so the colder the soil, the longer the sprout sits in the soil vulnerable to infection.

Two reasons to consider planting early are to try to increase yields or hit an earlier market window. However, a frost event after emergence can completely wipe out any advantage of early planting by setting crop development back for several days or more. If the frost is severe enough to kill the foliage back to ground level, the seed may also not have enough energy reserves available to produce another set of vigorous sprouts. In this situation there may be an advantage in planting slightly larger seed pieces.

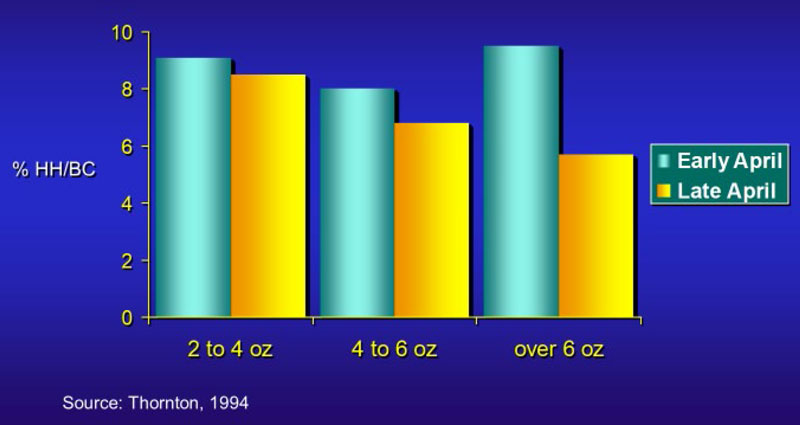

Soil temperatures below 55oF for 5 to 7 days during early tuber development can initiate brown center, which can turn into hollow heart under the right conditions. Early planting can move up the date of tuber initiation and increase the likelihood that tubers will be in the susceptible stage when soil temperatures are in the favorable range for brown center and hollow heart. Large tubers tend to show the highest incidence of brown center and hollow heart (Figure 5), emphasizing the importance of stage of tuber development at the time of exposure to incidence of this disorder.

Figure 5. Relationship between planting date (early or late April) and incidence of brown center and hollow heart.

Growers can reduce some of the risks associated with early planting by adjusting management practices to fit the situation. For example, use a good seed piece and in-furrow fungicide program to reduce seed decay and Rhizoctonia stem canker. Pay more attention than usual to warming seed prior to planting to encourage rapid emergence. Also closely monitor seed piece size and eliminate small seed pieces that are more prone to decay and do not have enough energy to withstand a frost. It is also important to manage planting accuracy to get a full stand and monitor nitrogen applications to reduce the potential for development of brown center and hollow heart. Finally, consider planting varieties with small vines and those that wound heal slowly at cold soil temperatures in the middle to end of your planting window to give them a better chance to sprout and emerge under more ideal conditions.

Early planting is one way to take advantage of projected high prices for early harvested potatoes, or to increase yield potential in short-season areas. However, growers should be aware that there are several risks involved that may reduce or eliminate any advantage from early planting and employ management practices to reduce those risks.