Story by Bill Schaefer & Dave Alexander

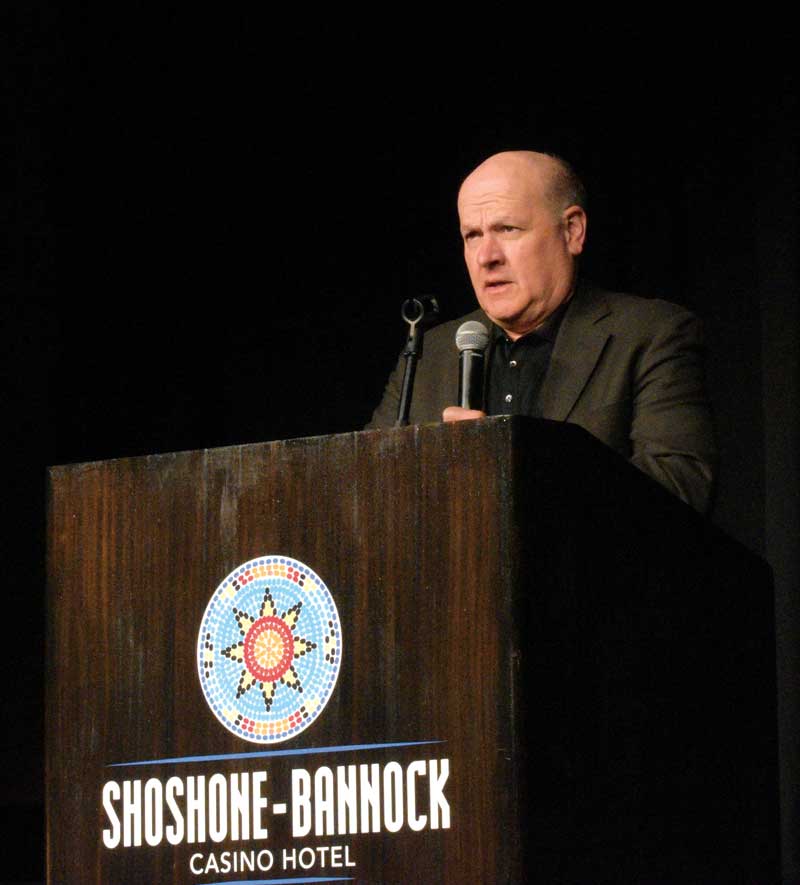

Frank Muir, Idaho Potato Commission president and CEO, speaks to roughly 225 attendees at the Big Idaho Potato Harvest Meeting in November.

The blast of arctic air that resulted in three nights of a hard freeze beginning on Oct. 9 was the proverbial icing on the cake for Idaho’s potato growers last year.

Travis Blacker, Idaho Potato Commission’s (IPC) industry relations director, described the 2019 growing season as one filled with contrary weather from planting to harvest at the IPC’s Big Idaho Potato Harvest Meeting in Fort Hall, Idaho, on Nov. 13.

“We had a lot of rain in the spring when we were planting, and pretty much from Magic Valley east, we had two different frost episodes,” Blacker said. “We were already thinking that yields would be affected by that, and then this frost hit on Oct. 9. But the good news is that when the frost hit, we think there was 85 percent of the crop in. That’s a lot of potatoes – good, quality potatoes.”

Blacker said that he had heard from some growers that last year’s crop, despite the delay in planting and the multiple frosts during harvest, is the best they’ve seen in at least 20 years and that the Russet Burbank crop was exceptional.

According to a recent crop production report released by the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Idaho’s yield is 435 hundredweight per acre (cwt), down 15 cwt from 2018. In the same report, NASS estimated that total production for 2019 would be 13.4 billion cwt, down about 5.5 percent from the 2018 production total of 14.1 billion cwt.

Ritchey Toevs (left) of Aberdeen, Idaho, receives the Idaho Grower of the Year award from Potato Grower magazine editor Tyrell Marchant.

You’ve Got to Market It

“This is a crop that will sell itself.” It’s a refrain Frank Muir has heard more than once since he became president and CEO of the Idaho Potato Commission in 2003. But Muir had a message for potato growers and shippers.

“Thirteen billion pounds of potatoes does not sell itself. You’ve got to market it,” Muir told the audience. “You have the perfect opportunity to keep the demand going and keep prices strong. This product doesn’t just magically sell itself.”

One of the messages to come out of the harvest meeting was that while Idaho’s total production and yield is down for 2019, the crop is a good one and Idaho has enough potatoes to meet demand.

“The last message we want to send is that Idaho doesn’t have any potatoes to provide all of your retail needs,” Muir said. “We will have sufficient potatoes to meet their needs.”

“I think all we’ve done with this freeze is take off the top of what could be a normal yield year,” Muir said. “What that does is that there’s no panic that we have a lot of potatoes to get rid of. The price has gone up. There’s been very strong, great returns for growers.”

Muir said the price for fresh market potatoes is positioned where he likes to see it coming into the current retail season and there’s no reason for prices to retreat.

Randy Hardy, a fresh potato grower in Oakley, Idaho, said his crop was looking really good prior to the cold spell and his Russet Burbanks were good quality and good size.

“We had a really good crop coming in my area, but we didn’t get some of the weather factors last spring that eastern Idaho did. But back here, we had a pretty good growing year,” Hardy said.

Hardy said the pulp temperature of potatoes was between 55 degrees Fahrenheit and 56 degrees two days prior to the freeze. Two days later, pulp had dropped to 37 degrees, he said.

“Those potatoes actually dropped 20 degrees in two days, and I don’t know that that has actually happened before to that extreme,” Hardy said. “What did it do physiologically inside to the potato, I don’t know. But we saw it warm back up to 50 degrees, 51 degrees. Then the next cold spell that came along, they dropped back down to around 40 degrees, 41 degrees, 42 degrees. That’s where we finished up. So I don’t know what’s going to happen to those. We’re watching them, and we’ll probably move them sooner than we anticipated.”

Hardy said he refers to a frost like this one as the gift that keeps on giving.

“You put them away in storage, you think you can dry them out, you think you can store them,” he said of the current situation. “You think you can sort them all out, and it just never is a very good situation. The frost, because it’s so much different than a bacterial rot, it’s going to be a real challenge for fresh guys as well as process guys.”

Hardy said he has heard that processors are looking for more potatoes in the fresh market to meet potential shortages during the coming year.

Mike Thornton with the University of Idaho explains that black spot and pressure bruise are the biggest quality issues.

Processors Cannot Keep Pace With Demand

Blair Richardson, CEO of Potatoes USA, echoed what Hardy said: processors do not have enough spuds. Traveling from Denver to speak to about 225 attendees at the harvest meeting, Richardson said that because potatoes are the most popular vegetable in the United States, demand is currently greater than supply. Broccoli was the top choice for consumers five years ago, but potatoes have become increasingly popular with U.S. consumers.

This surge has not only created a supply deficit, but processors are running full-bore to process the potatoes they have. Richardson described what he calls the “Minnesota Deer Season Indicator.” For the last 30 years, the Simplot processing facility in Minnesota has shut down two weeks of every year: Christmas and the opening of deer hunting season. This year, the plant remained open through deer season because it cannot keep up with the demand for frozen potato products.

Many of those frozen potatoes are French fries, now the number one side dish in American foodservice, according to a Potatoes USA study. Side salads were number two in the study, but number three is potatoes in any form. Richardson said the potato industry is winning at the consumer level, the foodservice level, in multiple categories and that “people do love potatoes.”

International demand is growing, as well. About 25 percent of the U.S. potato crop is exported, making the export market extremely important to growers. Of the exported spuds, 40 percent are fries.

The growth in frozen products and, therefore, the supply pressure on processors is directly tied to the growth in foodservice. Fewer people are eating at home and the majority of food dollars are spent in foodservice.

“People do not want to worry about cooking something at home. They want to go a restaurant, have it cooked for them, have it served to them and then go home and do whatever they are going to do afterward,” Richardson said, noting that 86 percent of frozen sales go to foodservice channels.

“This is an exciting time to be in this industry,” he said.

Kam Quarles, CEO of the National Potato Council, tells attendees at the Big Idaho Potato Harvest Meeting that “half of Big Potato is here,” referring to himself and Mike Wenkel, 50 percent of a staff of four.

Legislative Update

Kam Quarles, CEO of the National Potato Council (NPC), brought news and updates from Washington D.C. to the Idaho meeting.

“Our job is to bend federal and international policy to your benefit,” Quarles told the audience in describing NPC’s mission in his introduction.

Quarles touched on a number of legislative and regulatory issues currently being debated in Washington D.C. impacting the nation’s potato industry. He addressed the potential ratification of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), designed to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

“USMCA needs a House vote. We think the votes are there,” Quarles said. “Speaker Pelosi has to put it on the floor, and then the Senate should approve it fairly quickly. We just don’t want to let it linger into the election.”

Quarles then discussed the ongoing litigation to allow importation of U.S. potatoes throughout Mexico. Currently, U.S. potatoes are restricted to a 26-kilometer import zone at the U.S. border.

“Right now, we have several cases sitting before the Mexican Supreme Court,” Quarles said. “If there is a positive rule, it will empower the Mexican government to publish the necessary technical documents to allow fresh potatoes to be imported to the country.”

While waiting for Mexico’s Supreme Court to issue a ruling, Quarles said that Mexico’s avocado industry had recently petitioned the U.S. to allow more Mexican avocadoes into the U.S.

Quarles said that Department of Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue’s response to Mexico’s request was “no, I want to use this as a leverage to get American potatoes into Mexico.”

“It’s very simple,” Quarles said. “This provides the leverage to get this issue resolved once and for all, but we can’t lose that leverage and it needs to be used effectively.”

He said that once Mexico’s avocado industry realized that its petition for increased market access was being linked to the U.S. potato industry’s court case, the avocado industry became more of an ally for U.S. potatoes.

“And so an immediate reaction happened and they got more activated,” Quarles said. “They started talking to their government. Cables started flying back and forth. Meetings started happening. We need to continue to use that leverage. We cannot lose it. The administration is in the exact right place on this, and we need to see this all the way to the finish line.”

Quarles lauded past success in getting potatoes back into the school breakfast and lunch programs and cited Idaho Rep. Mike Simpson for his role in securing access for potatoes in the programs.

However, the program requires annual approval in the form of a public policy rider, and the NPC and a bipartisan group of legislators are pushing the rider forward, he said.

Once again, Quarles complimented Simpson and his congressional staff for their work in trying to move forward new and improved H-2A temporary agricultural worker legislation.

“Mr. Simpson has just done a tremendous amount of work, and his staff, in producing a very serious, bipartisan ag labor reform bill. It’s not a perfect bill. It’s a negotiated settlement,” Quarles said.

He said the legislation has a number of detractors and non-supporters, and passage through House, Senate and conference committee is going to be difficult.

“The big question right now is whether American agriculture can all bind together and move the process forward,” Quarles said. “There are very big players who are not supporting the House moving the bill through the process.”

Bruised and Frozen

University of Idaho potato scientists Nora Olsen and Mike Thornton updated the audience on their IPC-funded quality management studies on bruise reduction during harvest and storage.

Thornton said they’ve been monitoring quality notices that come from Walmart distribution centers across the country, and the majority of quality notices have come from seven distribution centers in the southeast corridor of the U.S. for the 2017 and 2018 crops.

“It points to the difficulty of shipping into areas with high temperatures and high humidity,” Thornton said.

He said black spot and pressure bruise seem to be the biggest quality issues annually.

Olsen also addressed storage issues for potatoes harvested following the October freeze.

“We can talk about the three days of frost, but we also had a lot of colder temperatures leading up to that and a lot of potatoes harvested outside of our traditional or recommended temperature ranges,” Olsen said. “So be aware that the quality all around this whole time may be impacted.”

Olsen advised growers to closely monitor those potatoes harvested and put in storage following the freeze.

“Be realistic about what those potatoes can do if you decide to move them through the packing system,” she said. “Prioritize, especially potatoes that are sharing a bay or sharing a plenum with your good potatoes. Decide where your greatest profit is and what you need to do to maximize that, and don’t compromise the good things to try to salvage what is potentially damaged.”

Whether the 2019 season is a profitable one for Idaho’s potato growers is still to be determined. One thing is for certain: 2019 has been a year that won’t soon be forgotten by Idaho’s potato industry.