By Amy Charkowski, Colorado State University; Stewart Gray, Cornell University; Russ Groves, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Alan Westra, Idaho Crop Improvement Association; and Mary Kreitinger, Cornell University

- Is a North American Certified Seed Potato Health Certificate available for this seed lot?

A North American Certified Seed Potato Health Certificate is available for each certified seed potato lot produced in Canada and the United States. It provides a certification number and information on required inspections and disease estimates based primarily on summer inspections in the current crop year. There is also information on the pedigree, origin of the seed lot and the number of generations it has been in the field. Buyers can request additional documentation such as field inspection, laboratory testing and WGO reports. If there are problems, the health certificate will help seed certification agencies identify the source of the problem, and it may help in management decisions.

Contact information for state seed potato certification agencies and links to certification regulations are hosted by the Potato Association of America (www.potatoassociation.org/research/seed).

- What were the post-harvest test results for this seed lot?

In addition to summer inspections, most seed potato lots produced in North America are subject to post-harvest testing (PHT), but methods, standards, and data reported and used for certification of seed lots differ by state. If uncertain, buyers can ask what’s included in the PHT. Generally, a 400-tuber sample is collected from each seed lot, but this number can vary depending on lot size. Most states perform post-harvest evaluations in Hawaii or Florida where the plants are visually inspected for obvious disease symptoms, herbicide damage and variety mixture; some laboratory testing may be performed to confirm Potato virus Y (PVY). Other states exclusively use laboratory testing and cannot providedata on herbicide injury, variety mixture or emerging pathogens for which routine tests were not completed.

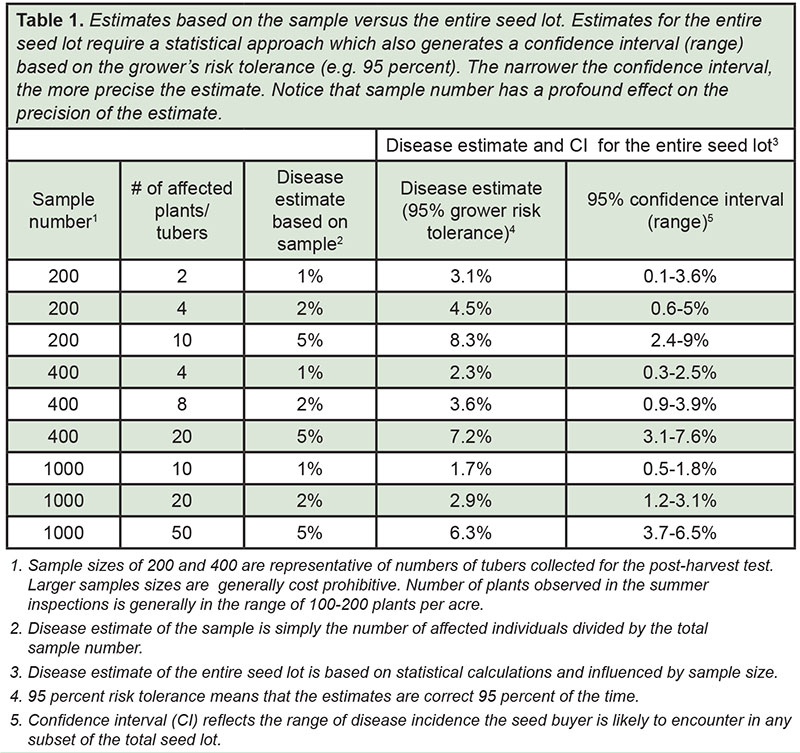

Do you wonder why the disease estimate reported on the health certificate is sometimes more (or less) than what occurs in your field? Estimates reported on the Health Certificate are the percent of diseased plants/tubers in the sample tested and are not an estimate for the entire seed lot. A tool for calculating the disease estimate for the entire seed lot is provided at blogs.cornell.edu/potatovirus/tools-resources. Use the tool and the information provided on the Health Certificate to calculate a more precise estimate of disease for a seed lot. Importantly, the precision of the entire seed lot estimate is highly dependent on sample size which is often not reported, but you can request this information. The greater the sample size, the more precise the estimate (Table 1).

- Was there bacterial ring rot found on your farm in the past year?

Bacterial ring rot (BRR), caused by Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus, is a serious disease that can be spread through seed potatoes. BRR is a zero-tolerance disease on seed potato farms, and infected seed lots cannot be legally bought or sold as there are no treatments to effectively control BRR once it has infected a plant. The pathogen spreads easily from infected to healthy tubers via contaminated seed cutters and pick-type planting equipment, and can lead to losses of 80 percent or more.

Bacterial ring rot causes foliar wilt, chlorosis and necrosis in the current growing season. Tubers show discoloration and necrosis of vascular tissue and central pith. Photos courtesy North Dakota State Seed Department

- Have there been reports of late blight in your area this season?

If yes, determine whether seed lots from the supplying farm are at risk of carrying late blight, Phytophthora infestans. Identify the strain (genotype) of the pathogen and ask whether it is resistant to metalaxyl/mefenoxam. Late blight is a particular concern when seed is purchased for use on organic farms since late blight management options are limited. Once a late blight epidemic has started in an organic potato field, crop destruction is often the only control option. In addition, late blight can spread across a community very quickly and destroy both potato and tomato crops.

- What methods were used to manage aphid-borne potato viruses?

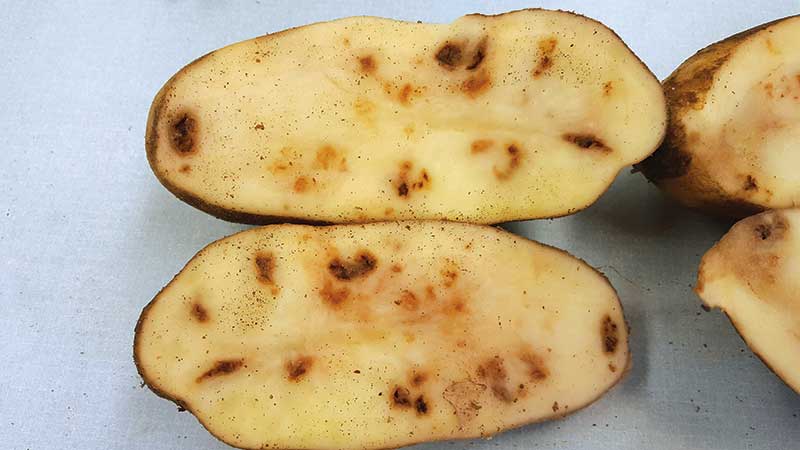

PVY and potato leafroll virus (PLRV), two aphid-borne potato viruses, can cause significant yield and quality losses in potato production. Both viruses can cause necrosis in tubers; PVY causes necrotic rings on the tuber surface while PLRV causes internal necrotic flecking.

PLRV is effectively managed by applying appropriate systemic insecticides at planting and supplementary foliar insecticides if colonizing aphids are found in the field. Transient aphid species do not spread PLRV, but they are responsible for most of the PVY spread that occurs during the growing season. Insecticidal control of transient aphids is ineffective, but mineral oil sprays can help if applied at the appropriate times and intervals.

PVY can cause necrotic rings on the tuber surface, as seen on this Yukon Gold. Photos courtesy Stewart Gray, Cornell University

- Was this seed lot produced in a field with a history of soil-borne viruses?

Two soil-borne potato viruses, potato mop top virus (PMTV) and tobacco rattle virus (TRV), are becoming more widespread and can cause significant losses. PMTV is spread by Spongospora subterranea, the soil-borne microbe that causes powdery scab. TRV is spread by the stubby root nematode. This nematode causes little damage on its own, but 100 percent losses can occur if TRV is present within resident nematode populations. PMTV, TRV and their vectors can persist in soil for many years, and management options are limited.

Seed certification does not currently test for these viruses, but seed lots generated on infested ground pose a high risk of infesting the buyer’s ground when planted, especially if the virus vectors are already present. Once established in an area, producers should practice sanitation of equipment to avoid movement of contaminated soil between fields, even during non-potato rotation years.

Tobacco rattle virus causes necrotic specks and arcs in tubers, while foliar symptoms are rare. Seed certification does not currently test for these viruses. Photos courtesy Yuan Zeng and Ana Fulladosa, Colorado State University; and Ken Frost, Oregon State University

- Was this lot exposed to herbicide?

Herbicide drift and carryover from previous seasons or from equipment that hasn’t been properly cleaned will reduce the productivity of seed potatoes. Seed potato herbicide injury can include tuber cracking, unusual root and sprout growth and very poor or delayed emergence of seed tubers. The tubers may also be more susceptible to decay in storage and in the field. Seed potato farmers should be both scouting for and taking precautions against herbicide damage in their seed potato crops. Lots with herbicide damage that will impact yield should not be certified.

Seed potato herbicide injury can include tuber cracking, unusual root and sprout growth and very poor or delayed emergence of seed tubers. Photo courtesy Amy Charkowski, Colorado State University

- Was any variety mixture detected?

Farmers who produce early generation seed potatoes may grow 20 or more varieties. Variety mixture can occur at many points during production. Variety mixtures may not be a significant problem if the contaminating tubers can be identified and removed during field production and grading; however, there is a low tolerance for mixtures that affect processing.

- What storage conditions were used for this seed lot?

Ideal storage conditions for seed are 38 degrees Fahrenheit and 95 percent relative humidity. As per certification regulations, seed potato farmers should clean warehouses prior to storing potatoes and should have protocols in place to ensure the seed potato lot identity is maintained throughout storage. Carbon dioxide levels need to be monitored; if too high, tubers can develop blackheart. Tubers with severe blackheart will not sprout vigorously and may not grow at all.

- Have you noticed any symptoms of tuber breakdown or soft rot?

Potato pathogens that cause tuber decay will spread quickly through a seed lot during planting, especially if the seed potatoes are cut prior to planting. Try to purchase seed potato lots that have not had blackleg (Dickeya spp.) in previous years and that have remained healthy throughout the winter storage season.

Symptoms of soft rot include sunken surface lesions and mushy, discolored interior tissue that ranges in color from cream to black and is often accompanied by a disagreeable smell. Photo courtesy Amy Charkowski, Colorado State University

Editor’s note: This material is revised from the Management of Potato Tuber Necrotic Viruses website. Visit the website (blogs.cornell.edu/potatovirus) for more information on potato diseases and management options.