By Kylie D. Swisher Grimm, USDA-ARS, Temperate Tree Fruit and Vegetable Research Unit

Tim Waters, Washington State University

Carrie Wohleb, Washington State University

In 2017 and 2018, disease-like symptoms were prevalent in potato foliage across the Columbia Basin of Washington and Oregon, appearing in July to early August and persisting throughout the season. Symptoms included leaf distortion with crinkled, warped leaves often found with small holes, purpling of upper terminal leaves, and stem damage seen as blisters and necrotic lesions.

In this region of the Pacific Northwest, several insect-vectored pathogens are known to cause leaf purpling of potato, including the beet leafhopper-transmitted virescence agent phytoplasma that causes potato purple top disease and Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum that is the causal agent of zebra chip disease. However, no pathogens are reported to cause severe leaf distortion or stem blisters and necrotic lesions.

During the 2017 and 2018 growing seasons in the Columbia Basin, healthy potato plants were difficult to find in affected fields, where symptom rates could be as high as 90 percent. Symptoms were observed across entire fields, so there was no edge effect or apparent foci that would typically indicate an insect-vectored pathogen was causing the symptoms. Symptoms were not observed in tubers harvested from these symptomatic fields, and there was no apparent reduction in tuber yield reported.

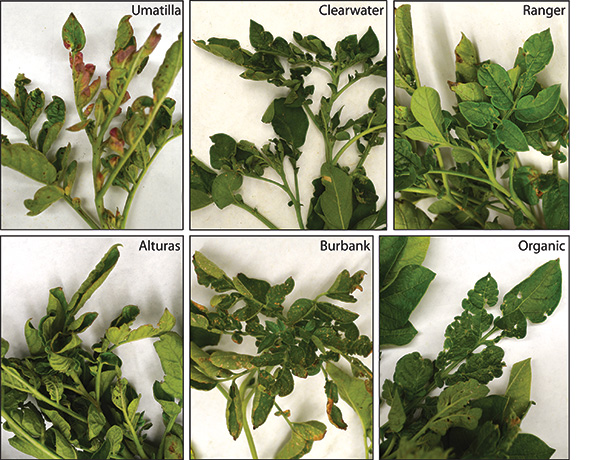

Differences in symptom timing and development across cultivars were readily apparent throughout the Columbia Basin. Umatilla Russet consistently showed the most severe symptoms, with leaf distortion, terminal leaf purpling and stem lesions evident across entire fields by mid-August. At this same time, foliage of Clearwater Russet generally looked healthy, though leaf distortion and the initiation of leaf purpling was visible across all observed fields. Clear leaf distortion and stem lesions were observed in the Alturas and Ranger Russet cultivars in late July and mid-August, respectively, but very little purpling was seen. Foliage of the Russet Burbank cultivar was surprising, showing only very low levels of leaf distortion and stem lesions in mid-August.

In 2017, an organic potato field was observed with low levels of stem lesions and moderate to severe levels of leaf distortion, indicating chemical damage was not a likely cause of the symptoms observed across the Columbia Basin.

The widespread nature of these disease-like symptoms in the Columbia Basin prompted researchers at the USDA-Agricultural Research Service in Prosser, Washington, and Washington State University, with funding from the Northwest Potato Research Consortium, to determine if a pathogen could be causing these symptoms. Foliar tissue and tubers were collected from different cultivars across the Columbia Basin in 2017 and 2018 for analysis. Molecular diagnostics and greenhouse grafting of diseased tissue were performed simultaneously in an effort to identify a cause of these symptoms.

Molecular Diagnostics

Terminal leaf tissue from plants of each potato cultivar collected from Columbia Basin fields in 2017 and 2018 was analyzed for the presence of common viral and bacterial pathogens using standard molecular tools. No pathogens were identified that correlated to the disease-like field symptoms present in all samples collected. Similarly, tubers collected in 2017 were tested for common pathogens, and no pathogens associated with the disease-like symptoms were identified by molecular analyses.

In both 2017 and 2018, the foliage from four plants collected from either commercial fields or research plots in the Columbia Basin tested positive for beet leafhopper-transmitted virescence agent phytoplasma. This phytoplasma is known to cause potato purple top disease in this potato-growing region of the Pacific Northwest. However, since the majority of the plants demonstrating the mysterious symptoms were negative for potato purple top disease, purple top is not considered to be the primary cause of the symptoms.

Symptom development was not consistent between all cultivars examined, with Umatilla Russet showing the most severe symptoms in both 2017 and 2018.

Grafting Analyses

To determine if the disease-like symptoms present in the field could be transmitted to healthy plants, indicating the presence of a pathogen, field-collected tissue was grafted to healthy plants in the greenhouse. Here, symptomatic tissue from roughly 100 different plants was spliced into stems of individual healthy potato plants to allow movement of nutrients between both tissues. The healthy recipient plants were observed on a weekly basis for symptom development.

Most grafted plants showed no symptom development more than 40 days after grafting, indicating the movement of a potential pathogen was not occurring. Plants that did show symptoms were associated with potato purple top disease, which was not unusual due to its known occurrence in the area. In both years, field tissue that tested positive for beet leafhopper-transmitted virescence agent phytoplasma in the laboratory showed graft transmission of these purple top disease symptoms, with aerial tuber development and terminal leaf purpling and curling.

The successful transmission of phytoplasma in a small subset of the grafted plants shows how effective this technique can be for observing pathogen-induced foliar symptoms. It also highlights the absence of pathogen transmission in samples grafted with tissue displaying the mysterious disease-like symptoms.

Symptomatic tissue was grafted to healthy potato plants in the greenhouse at the USDA-Agricultural Research Service in Prosser, Wash. Most grafted plants did not show transmission of a pathogen (left), though plants grafted with beet leafhopper-transmitted virescence agent phytoplasma-infected tissue did (right). Red arrows indicate the grafted field tissue (scions); white arrows indicate development of purple top symptoms on the healthy recipient plant.

Tuber Grow-out

A total of 46 tubers collected from four different commercial fields and research plots where plants exhibited the mysterious foliar symptoms in 2017 were planted in the greenhouse to inspect the emerged tissue for symptom development. No symptoms of leaf distortion, purpling terminals or stem lesions were observed on the emerged plants. These results indicate the disease-like symptoms are not likely transmissible through tuber seed pieces.

Results from this two-year study strongly indicate the mysterious foliar damage seen in potato plants across the Columbia Basin in 2017 and 2018 was not caused by a pathogen. The inability to detect a known pathogen in symptomatic tissue in the laboratory, combined with the lack of symptom development in healthy recipient plants grafted with symptomatic field tissue and the lack of transmission through tuber seed pieces, provide convincing evidence the causal agent of the region-wide symptoms was not pathogenic in nature.

While it does not appear tuber quality or quantity is greatly impacted by the above-ground foliar symptoms, further research is still warranted to determine the cause of these symptoms. It is possible an environmental stimulus, mechanical damage (such as insect feeding) or even the injection of an insect toxin could be causing these disease-like symptoms in the Columbia Basin, and identifying this agent or factor could improve management strategies to help prevent these symptoms in the future.