by Bruce Huffaker, Publisher, North American Potato Market News

USDA indicates that U.S. growers produced 436.4 million cwt of potatoes in 2017. That is 3.1 million cwt less than they produced in 2016, a 0.7 percent decline. The total includes a 4.6 million cwt increase in early-season potatoes to 38 million cwt. USDA puts the fall potato crop at 398.9 million cwt. That falls 7.7 million cwt short of 2016 production, a 1.9 percent reduction.

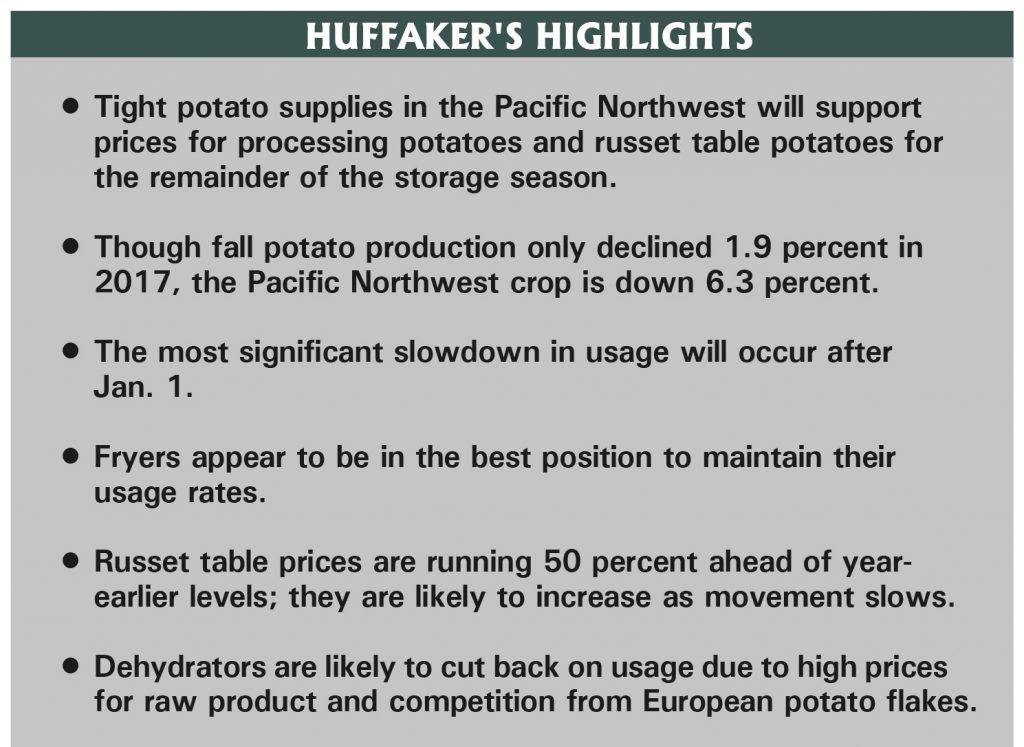

Industry experts question whether USDA’s crop estimates reflect the true extent of this year’s production cutbacks. Even if they are accurate, the production data do not reflect the shift in production between industry market sectors. Fryers are scrambling to line up enough potatoes to keep their plants running until the 2018 harvest gets underway. Shipping point prices for russet table potatoes are running 50 percent ahead of year-earlier prices across the Pacific Northwest. On the other hand, storage chip potato supplies are plentiful, and prices for red and yellow potatoes are running 10 to 20 percent below year-earlier levels in Colorado and in the Midwest. The unbalanced supply situation creates the potential for further strength in markets for open russet potatoes during the next six to nine months.

Pacific Northwest Supply

The Pacific Northwest appears to hold the key for russet potato markets during the remainder of the 2017-18 storage season. Idaho, Oregon and Washington combined to produce 251.1 million cwt of potatoes in 2017. That is 16.8 million cwt less than those states produced in 2016, a 6.3 percent decline. Growers held more storage potatoes at the beginning of June, but those potatoes cleaned up quickly. There is no evidence that regional potato disappearance has slowed down during the early part of the season. The region’s Dec. 1 potato stocks are likely to fall at least 9 percent short of year-earlier holdings. (USDA released data on Dec. 1 potato stocks on Dec. 19 after our press deadline.)

The lack of any slowdown in Northwest potato usage between June and November will crunch this year’s supply shortfall into the last half of the marketing year. The industry could hold the December-May usage decline to 9.7 million cwt by pulling June 1 stocks down to 31.4 million cwt, a 16.7 percent decline from last year. However, at the anticipated December-May usage rate, stocks at that level would equate to a 43.9-day inventory. That is the lowest inventory, relative to daily usage, since 2006, which indicates that supplies would continue to tighten until the 2018 harvest ramps up.

The Pacific Northwest potato supply crunch will impact all sectors of the potato industry. However, market forces will determine which sectors cover their needs and which come up short. Buyers in three sectors, table potato interests, fryers and dehydrators, will be competing for the available supplies. Demand parameters vary significantly by sector.

Sectors Competing for Supplies

Average russet table potato prices have fallen short of production costs for three consecutive years. That prompted growers to limit acreage for the 2017 crop. Those acreage cuts were modest, but when Idaho dehydrators cut back on field-run contracts, the industry expected growers to substitute dual-use varieties rather than switch to other crops. That didn’t happen. The processors’ miscalculations are a major factor in this year’s supply shortfall. Fryers have lined up supplies to offset as much of their shortfall as possible. That has included purchases of Russet Burbank potatoes from grower-shipper operations, further limiting supplies of russet table potatoes.

A 50 percent increase in average shipping point prices, relative to last year, reflects the tightness in table potato supplies. However, the impact on shipments, through the end of November, has been limited. Idaho’s fresh shipments from the 2017 crop are down 1.1 million cwt from year-earlier movement, but close to half of that shortfall has been offset by late-season shipments from the 2016 crop. USDA data suggest that shipments from the Columbia Basin and Oregon have been keeping pace with year-earlier movement, while shipments from the Skagit Valley are up significantly. (Please note that the Washington shipping data reported by USDA are questionable.) Supplies available for shipment after Jan. 1 will be limited, which is likely to result in further market strength.

Fryers have added capacity in the Columbia Basin this year. There is demand for more product than the fryers can run through their plants. As noted, they have lined up open potatoes to cover a portion of the raw product shortfall. However, that is unlikely to be sufficient to cover sales. They may be in the market for more raw product if they can find potatoes that will fry and meet other customer requirements. In addition, they are pushing growers to plant more early potatoes and are hoping that those potatoes will be ready for an early start to the 2018 harvest. We are not sure what the price limit will be for open potato purchases. However, we understand that some potatoes have changed hands at prices as high as $9.25 per cwt for use during November and December. Fryers are in a good position to bid raw product away from both fresh packing operations and dehydrators. They also are likely to reduce finished-product inventories to pipeline minimums.

The dehydrators’ lowest-cost raw product is off-grade potatoes from the table potato sector. While a few of those potatoes may be acceptable for fresh sales, most have no other outlet. That is particularly true when supplies of table potatoes exceed demand, as has been the case for the 2014-2016 potato crops. Three years of surplus process-grade potatoes encouraged dehydrators to cut back on field-run contracts for the 2017 crop. Uncertainties regarding the operations of certain plants resulted in additional cuts.

When prices are high, table potato shippers attempt to recover a larger portion of the potatoes that they run. With fewer fresh potatoes to run, and a higher pack-out rate, process-grade potato supplies available for dehydration will be much less plentiful than they have been in any of the last three years. Dehydrators will have the option to compete against table potato interests and fryers for open potatoes, but costs are likely to be much higher than they have been for the past three years. Dehydrators will limit usage to their minimum needs. They will be competing against cheap European product, both in the export market and in some domestic markets. As a result, their potato usage could fall significantly short of last year’s pace.

Editor’s note: To contact Mr. Huffaker, or to subscribe to North American Potato Market News (published 48 times per year), write or call: 2690 N. Rough Stone Way, Meridian, ID 83646; (208) 525-8397; or e-mail napmn@napmn.com.